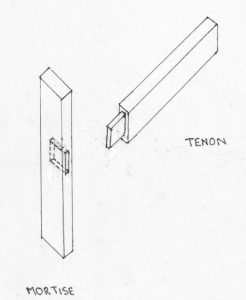

MORTISE & TENON JOINT

MORTISE & TENON JOINT

by Louis Mulder

About the author

I was one of the privileged individuals who had woodwork as a school subject, right up to Matric. Wood, and working with wood became part of my lifestyle, something I would never like to ever change. Over the years I had made several items, never intending to do mass production, but rather make something that would be a unique piece of craftsmanship that I could give or sell to someone. Because of the fact that wood is such a versatile medium to work with, I just fell in love with it, and every time I enter my workshop, it is like a new adventure starting for me!

Introduction:

Of all the wood joints that are used in making furniture, I believe that the mortise & tenon joint is the strongest of them all. Its’ uses have no limit, although is commonly used in making door-frames, tables, chairs and panels.

The strength of the joint depends on how well it was made. This is normally observed when you dry-fit the joint, i.e. testing the joint. If the joint is too tight, it might happen that the tenon breaks, or split open the wood where the mortise was made. On the other hand, if the joint is to loose, and you have to pack the joint with bits of wood to make it tighter, you will have a weak joint. A good, well–made joint is one where you can push the tenon into the mortise with only using your hands, which is called dry-fit, i.e. checking the joint before it is glued together.

Safety:

Whether you are a newcomer to woodwork or more experienced, like myself, one should always have safety in mind. You are going to work with sharp tools: chisels, saws, planes, to name but a few, and as you grow with knowledge, you will be adding power tools of all sorts. Don’t let your tools become your enemy; you want to walk out of your workshop after a project with both hands, feet and eyes.

- Never try to keep a piece of wood in your one hand and attempt to use a chisel or saw with the other hand to do something to the wood. You either clamp the work to your workbench or workmate or in the vice of you workbench or workmate.

- Never allow kids to play in you workshop.

- Speak to your family, and if possible, put up a signboard in you workshop, not to be disturbed or shout at while doing some work with tools. The moment you are distracted, that is when accidents happen, like cutting your hands or fingers.

- Use eye protection. A pair of goggles that even will fit over you own glasses, if you wear glasses, is sufficient. A splinter in your eye is not the way you want to finish a day between your tools!

- Never do any woodwork if you are using medicine that makes you drowsy, or if you had liquor of any kind.

Tools:

The basic tools that you will need to do this exercise is: a try square, set of bevel edge chisels, mortise gauge, mallet, wood bench or Workmate, ruler or measuring tape, sharp pencil, a marking knife (a six inch nail will also work) a backsaw and a mitre box.

Timber:

Always buy your timber at a reputable dealer. Inspect the wood for warping and cracks. For beginners, I always suggests to start working with a soft wood like Pine or Meranti, because it is easy to work with and also not so expensive than your harder woods like Imbuia, Kiaat and Stinkwood.

Measuring out the mortise

For the purpose of this exercise, I will show you how to make a mortise & tenon joint, using only hand tools. In the world of woodworking today, woodworking is done in the most cases by using machinery, because the industry requires quick turnovers which are mostly focused on mass production. However, you have the companies that focus on high quality furniture with distinction, for which a lot of hand tool work is needed to be done by high class craftsmen. Therefore, for anyone who is serious in becoming a skilled craftsman, start with hand tools and learn everything about the trade, using different joints, until you are ready to add the comfort of machinery to your projects.

So we are going to start to measure out the mortise.

With the side into which I am going to make the mortise, facing up, I decide where the mortise will be. For easy understanding I will call this piece of wood M for mortise, and the tenon piece will then be referred to as T. Lay piece T across over piece M at the place where the mortise will be, and mark the width of piece T on piece M. The wood I am working with for this exercise is 45 mm wide by 20 mm thick. Now I use my try square and draw the two lines where I marked out the width. Use your ruler now to measure 6mm in from each pencil line on piece M, which will be part of the “resting place” for the shoulders of the tenon.

Now it is time to use the mortise gauge.

In most cases, the mortise is one third of the thickness of the tenon piece, but because my smallest chisel is a 6mm, I am going to set the mortise gauge on 6mm for the mortise, and then 7 mm from the head of the mortise gauge to the first pin of the mortise gauge. Take piece M and hold one piece on your workbench or workmate while lifting the other side of wood up towards your body. Let the head of the mortise gauge now slide along the side of piece M until the two steel pins touches the wood. Start to scrape between the two inner pencil lines, using a little hand pressure, until two thin furrows is visible in the wood. Use your pencil to highlight these little furrows. The mortise will now be clearly visible between the four pencil lines and we are ready to start chiseling it out.

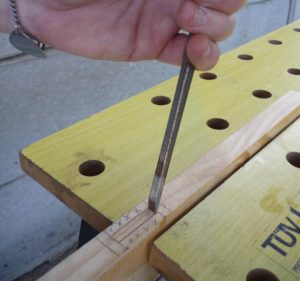

You will start off with putting the chisel on the inside pencil line of the mortise, with the bevelled side of the chisel, facing inwards. Hold it at 90 degrees, and hit the chisel with the mallet. Now put the chisel on the inside pencil line on the other side of the mortise, and hit the chisel with the mallet.

On inspection of what you just did, you will see that the bevelled edge of the chisel has forced the wood away from the two pencil lines, and that is what we want in order to get a neat mortise. Continue now to chop out the mortise, working from one side to the other, reversing the chisel in the process. As you go deeper into the mortise, start to check the depth. The tenon will be 25 mm (the guideline for a tenon is two thirds of the width of your mortise piece, which in this case is 45 mm.) This is very easy to do: press your chisel down in the mortise, keep your finger where the chisel meets the edge of the mortise, and measure the distance. In this way you can ensure that you don’t go to deep by accident and perhaps go right through and out on the other side. Once you are satisfied that the chiselling of the mortise is completed, check the mortise, and if you see little humps on the inside of the mortise, use a chisel with a wider blade to carefully shave off the humps. Please note that this is a normal action after chiselling out of a mortise and not because of a wrong technique on your side.

Laying out the tenon:

This is our piece T that we will now work with. Lay the piece down flat on your workbench or workmate, and measure 25 mm in from the one side of the piece.

Use the try square and draw lines around the piece on all sides, making sure that the lines connect at the corners with each other.

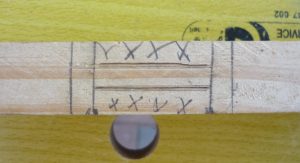

While lifting the back of piece towards your chest for ease of handling, start to scrape from the first pencil line towards the end of the piece, making sure that the mortise gauge is held firmly against the width of the piece. Now put the piece down, hold the mortise gauge still in place and scrape over the end grain, then lift up the piece, and continue scraping on the other side, from the end of the piece up to the pencil line. On inspection, you will see the same thin furrows, as we had when making the mortise. Take your sharp pencil, and highlight these furrows so that they are more visible. The next thing that I always do when making tenons, is to make a lot of x’s on the waste sides of the tenon with my pencil so that when you start with the sawing out of the tenon, you don’t get confused and make a mistake that will cost you dearly.

We are now ready to saw out our tenon. Before we start, a bit about using the backsaw in a case like this:

- Make sure your saw is sharp and clean.

- Don’t hang with your body over your work and make sure your piece of wood is secure into your workbench vice or the jaws of your Workmate.

Take the saw in your hand; get in behind your Workmate or workbench so that your body, arm and the work piece, is in one line with each other.

This way, you can see your work properly, and will also see where the saw blade is going to. If your position is skew, chances are that you will also saw skew. Position piece T vertical in the vice or Workmate and tilt it forward. Start your cut on the scraped/pencil line, making sure that you stop at the pencil lines that was drawn all around the piece. Bring the piece up so that that it is in a 90 degree position with your workbench or workmate, and complete the cut, again make sure that you stop at the pencil lines.

Turn the piece around, position again in the vice or workmate, and continue with sawing of the second cut, like with the first one. When finished, lay piece T flat on your workbench or workmate and with your try square on the pencil line, scrape with your marking knife over the width of the wood, turn the piece over and do the same on the other side.

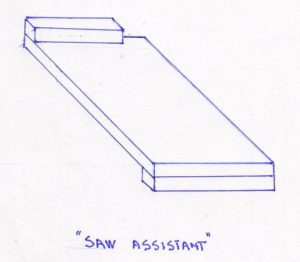

The purpose of this action is to provide a little furrow into which the saw blade can fit, to prevent slipping of the blade. It makes sawing a great deal easier. For the next action, namely to cut the two shoulder lines, I use a mitre box, but I think it is a good idea for the beginner to make himself a cheap “saw assistant”, that is basically a flat piece of timber, for example 200 mm wide by 250 mm in length, with a batten of 40 mm by 40 mm by 170 mm screwed to the top part of the timber, and another batten of 40 mm by 40 mm by 200 mm, screwed to the bottom, reverse side, of the timber. The idea is to clamp the bottom part in your vice or Workmate and then you have a sturdy “saw assistant!”

This is the gadget that we used at school, and the reason I like it, is that it teach you to saw straight and accurate, one of the fundamentals of good woodworking. So whatever you will be using, start to saw on the shoulder lines, taking care not to cut into your tenon.

With this done, you should be left with a perfectly sawn tenon. All that is left now is to saw the cheeks on the tenon. With the piece position in your vice or Workbench, mark in 6 mm from the sides of the tenon.

With your try square draw lines over the end as well as both sides of the tenon. Hold your backsaw firmly and saw down to the shoulder lines. With both cuts completed, put the piece in your vice or workmate and finish the cheek cuts.

The last action that is left is to check for fit.

If you have been following all the steps, you should have a perfect mortise and tenon joint. If not, don’t despair.

Remember: perfection only comes through repetition!

Comments

Add comment